|

| The Pantheon on Rome's birthday, © Tiffany Parks |

Is the Pantheon a sundial?

The Pantheon is one of the most recognizable monuments in the Eternal City and receives millions of visitors every year. Any guidebook will tell you that the temple was built by Emperor Hadrian around 126 AD, that it’s the best-preserved ancient Roman building in the city, and that the early Renaissance architects studied it for insight on building domes. Its most characteristic aspects include a coffered ceiling, the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world, and an oculus—or open hole—in the ceiling that illuminates the dark interior with dramatic shafts of light.

But recent studies have hypothesized that the iconic site is even more than meets the eye. Historians Robert Hannah and Giulio Magli claim that the true purpose of the Pantheon was nothing less than an enormous sundial, having been oriented so that the sunbeam from the oculus lights up certain areas of the interior at significant times of the year. And in fact, the light beam shines directly out the door at noon on 21 April, the legendary founding of the city, and in other striking ways on solstices and equinoxes. Other scholars disagree, saying that the purpose of the oculus was to cool the building in the heat of summer, or lighten the weight of the immense dome to prevent collapse. But without concrete evidence, the true purpose of the Pantheon will remain one more of Rome’s unsolved mysteries.

Piazza della Rotonda. Open Mon–Sat, 9am–7:30pm; Sun, 9am–6pm.

|

| Basilica Neopitagorica |

What was the Basilica Neopitagorica used for?

Located directly below the tracks of a railroad line that connects Rome and Naples and buried entirely underground, the Basilica Neopitagorica is one of the most mysterious and little-known sites in the city. The mysterious building lies nearly nine meters under Via Prenestina, and is laid out in the classical basilica plan, with three naves, an apse, an atrium, and a dromos. The barrel-vaulted ceilings are decorated with stucco reliefs depicting mystic symbols, the floors are covered with traces of black and white mosaics, and frescoes along the walls depict scenes from Greek mythology.

But no one knows for sure what this cryptic space was used for, and multiple theories have been put forth since its accidental discovery in 1917. Some claim it was a nymphaeum, others insist it was a mausoleum or funerary complex dating to the late-Augustan period. The most widely held belief is that it was a sanctuary of the Neo-Pythagorean cult, a philosophic and religious movement inspired by the teachings of the Greek thinker Pythagoras. The cult eventually died out in favor of Neo-Platonism, and the basilica appears to have been destroyed during the reign of Emperor Claudius.

Although it is now entirely excavated, the site has long been inaccessible to the public, mostly due to its precarious position beneath the railway line. However, it opened its doors for a limited series of visits this past fall, and although those visits are now over, we can only hope that they decide to do so again in the near future. Especially as this one’s on my bucket list.

Piazzale Labicano. www.coopculture.it

|

| San Lorenzo Fuori le Mura |

Is the Holy Grail in Rome?

Everyone knows the story of the mystical Holy Grail and the numerous lifelong quests to discover its location, or even confirm its very existence. From King Arthur to the Knights Templar to Indiana Jones, every great adventurer has dreamed of holding the sacred chalice in his hands. But what if this most sought-after of artifacts were right here in Rome, under our very noses? That’s what archeologist Alfredo M. Barbagallo claims. Christian tradition would have it that the treasures of the early church were entrusted to St. Lawrence by Pope Sixtus II in 258 AD. Was it a coincidence that the saint was martyred just four days later (famously grilled alive) during the persecution of Emperor Valerian? Barbagallo says no. He believes that St. Lawrence took the grail with him to his grave, on top of which was built a small shrine, and later the Basilica San Lorenzo Fuori le Mura. Go ahead and visit for yourself, but keep in mind that the catacombs under the church remain sealed. Until they are opened, we’ll never know for sure.

Piazzale del Verano, 3. Open daily, 7:30am–12:30pm and 3:30–7pm.

|

| The Colosseum by night, © Alessandro Silipo |

Is Rome truly haunted?

In a city that has seen as much death as Rome has, there are bound to be a few ghosts flying around. From the thousands of people slaughtered in the Colosseum, to the medieval plagues that carried away 90% of the population to the Sack of Rome of 1527 that claimed up to 12,000 lives, the scent of death has been a constant in the Eternal City since its inception. For centuries, it was believed that the Colosseum was one of the seven portals to hell, rife with demons. Artist Benvenuto Cellini wrote in the 16th century of his experience consulting with a necromancer at the Colosseum, seeking to discover the fate of his missing lover. As late as the turn of the last century, the Colosseum was thought to be so polluted by the noxious fumes of its countless murders as to be fatal to anyone who breathed them, particularly at night. (Just read Henry James’ Daisy Miller if you don’t believe us.) Decide for yourself if it’s truly haunted by taking an after-hours tour, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Piazza del Colosseo, 1. www.coopculture.it

Want more solid proof of the existence of ghosts? Pay a visit to the Museum of the Souls in Purgatory, a tiny museum that displays messages from beyond the grave: fingerprints burned into prayer books, a charred handprint on a wooden table, and other creepy evidence that heaven’s unpleasant waiting room might actually exist.

Lungotevere Prati, 12. Open 7:30–11am and 3:30–7:30pm.

|

| David Oakes as Juan Borgia and Francois Arnaud as Cesare Borgia in Showtime's series, The Borgias |

Did Cesare Borgia kill his brother?

The infamous Borgia clan: they were rich, powerful, corrupt, violent, and Spanish. Led by the charismatic and sensual patriarch Rodrigo Borgia, who was elected Pope Alexander VI in 1492, they were the most hated and feared family in Renaissance Rome. Scandal followed wherever they went, and not without good reason. The Pope had at least 11 illegitimate children and celebrated his ascension to the throne of St. Peter by acquiring a new teenaged mistress. Two of his children, Cesare and Lucrezia, were accused of having an incestuous relationship, and his Master of Ceremonies Johannes Burkhart reported elaborate orgies taking place inside the Pope’s apartments. But by far the greatest scandal of his papacy was the death of the family golden child, Juan Borgia, when his body mysteriously washed up on the shores of the Tiber with its throat slit and nine stab wounds to its torso. He was hated by so many people that it was impossible to identify a killer, although many scholars believe one of his own brothers did the deed, most likely Cesare, jealous of their father’s favor and their sister’s affections. After more than 500 years, the trail has gone a bit cold, and it’s unlikely we’ll ever know for sure who killed Juan Borgia. But a visit to the Borgia Apartment (part of the Vatican Museums), with the nefarious family members immortalized in frescoes by Pinturicchio, will make the mystery come alive. And keep your eyes peeled for the trap door that reportedly exists somewhere within it, a hatch that emptied directly into the Tiber, making it all too easy for the Pope to dispose of his enemies.

Viale Vaticano. Open Mon–Sat, 9am–4pm. www.vatican.va

|

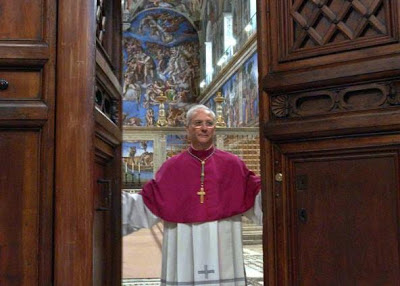

| Pope John Paul I, August 1978 |

|

| Pope John Paul I, September 1978 |

Was John Paul I murdered?

A slightly more recent Vatican whodunit concerns the fate of Pope John Paul I, whose pontifical reign lasted a mere 33 days. Elected on 26 August 1978, he was found dead in the early hours of the morning of 29 September, barely a month later. Official Church spokespeople insisted his death was natural, although some reported heart attack and others said pulmonary embolism, others still claimed an accidental overdose of his medications. It would later be impossible to confirm, as his body was embalmed immediately, with no autopsy. Not only that, but the Pope had no history of heart issues, his personal items disappeared, never to be seen again, and it eventually came out that the nun who had discovered his body was placed under a vow of silence. Many suggest there was, in fact, a more sinister explanation behind his untimely demise, perhaps because Papa Luciani (as he was affectionately known) did not always adhere to the conservative Vatican line, and his fervent goal was to rid the echelons of the Church of its wealth and power. Not very convenient for the big dogs in the Vatican curia. To learn more, pick up a copy of In God’s Name, a work of nonfiction by investigative journalist David Yallop.

|

| Johanna Wokalek as the title character in Pope Joan (Constatin Film) |

Was there really a female pope?

A mystery that is sure to remain unsolved, probably for all time, is that of Pope Joan, the supposed female pope. The story goes that, during the early Middle Ages—the 9th century according to most accounts—a young Saxon woman who was unusually well educated for the time, disguised herself as a man and became a monk. She later travelled to Rome where she ascended the church hierarchy and was eventually elected pope. She ruled for two and a half years, but was discovered when she gave birth unexpectedly during a papal procession, and died shortly thereafter. The earliest reports of this extraordinary tale don’t appear until the 13th century, and for this reason, many naysayers reject the story out of hand. But while the story of “la papessa” officially holds legend status, there are those who wholeheartedly believe she existed. Their number one piece of evidence is a wooden chair—reportedly hidden away in the archives of the Vatican Museums—with a keyhole shape cut out of its seat. During the middle Ages, newly elected popes would be asked to sit on the chair, while a cardinal checked to make sure they were indeed male. Intrigued? Pick up Donna Woolfolk Cross’s historical novel Pope Joan, or the 2009 film based on the same.